One of the biggest sectors of the economy today is going through massive disruption through innovation. This isn’t something to be taken lightly.

I don’t mean banking and fintech; it’s not Detroit and electric cars; it’s not even media and online streaming. It is so pervasive that many people seem to forget it even exists, because it’s happening constantly right before our eyes.

It’s consumer products and retail.

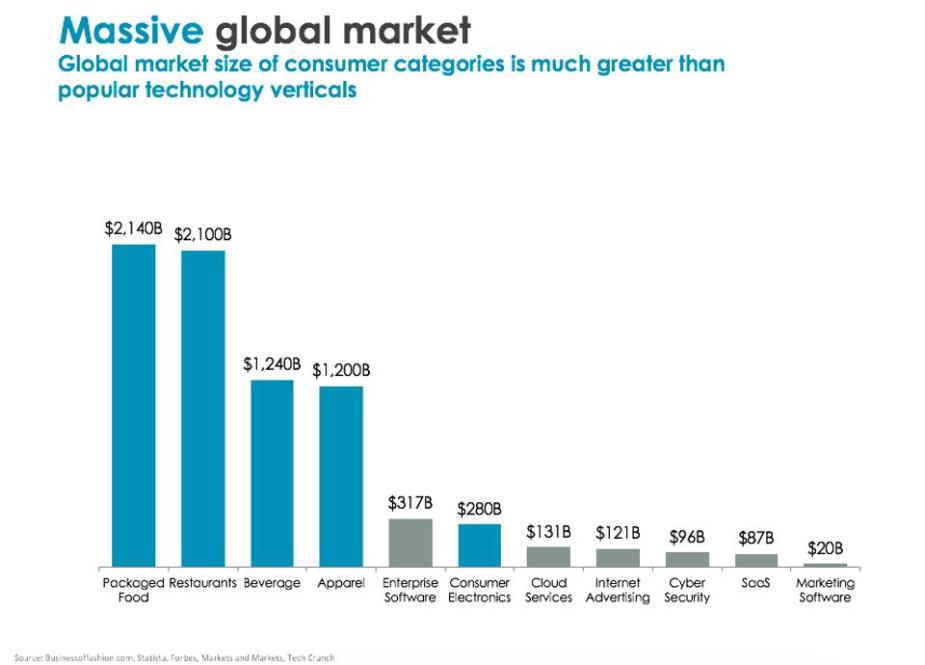

The various categories of consumer are some of the largest segments of the economy: Packaged foods is a $2.14 trillion industry globally; Beverages is $1.24 trillion; Apparel is $1.2 trillion. By comparison, enterprise software is a $317 billion category. Internet advertising? A meager $121 billion.

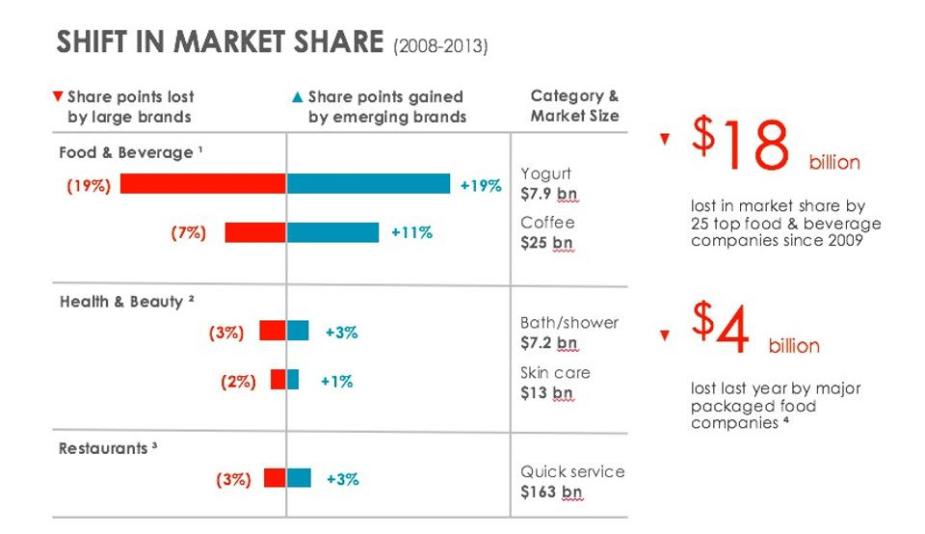

Consumer and retail is huge, and it is making tremendous progress that is completely transforming the landscape. The large, once-dominant players are stumbling. In the 12 months ending June 2015, 90% of the top 100 consumer brands lost market share. This has some of America’s most iconic brands terrified.

There have been many missteps that led consumer and retail players to lose share while young brands in almost every consumer packaged goods category have pulled ahead. But, when we closely observe the disruption happening in this industry, we see three primary forces driving this change. The personalization of consumer, democratization of distribution, and emergence of new growth levers have shifted the powers from the legacy consumer brands to millions of newer, small brands.

1. Personalization of the Consumer

Millennials are demanding more personalized product offerings. As I’ve discussed before, they want products that meet their unique preferences, be it organic, vegetarian, ethnic, sustainable, just as their iPhones offer limitless unique services. Speaking of iPhones, just as millennials don’t want to use the dial up phones their parent did, they don’t want to buy the same makeup their mothers bought or eat the same cereals they fathers ate. This isn’t simply a quality issue where the middle grocery aisle products aren’t up to snuff, it’s a personalization issue. Now, the seemingly simple act of selecting home cleaning solutions is a form of self-expression. Instead of processed sugar and carbs, millennials want, and are able to get, gluten-free, natural, high-protein, vegan, high-fiber. The good old gallon of milk has gone sour, replaced by soy, almond, hemp, rice and coconut milks. Millennials could very well drive 75% of growth in food and beverage over the next decade, and they demand something authentic and personal.

The problem is that large strategics like Unilever , Pepsi , Clorox CLX -1.12% and McDonald’s struggle to create the products and brands that meet these demands. A large investor recently wrote to me saying “if you want a real life example of what might happen in consumer products, look no further than McDonald’s earnings today. They have an amazing supply chain which has yielded higher company-operated contribution margins – and a bad product.” McDonald’s earnings and stock price are down. While massive brands focus on driving efficiency, consumers are moving towards better products, like Shake Shack, as well as small brands in coffee, yogurt, personal care and more.

2. Democratization of Distribution

New distribution channels support unique offerings better than ever before. Former distribution models, dictated by big retailers, are collapsing. Retailers like CVS, Safeway SWY +%, Krogers, Walgreens, Nordstroms and Neiman Marcus have for years favored the largest consumer products companies, because those were the ones willing to pay outlandish fixed fees, sometimes known as slotting fees, to get products on the shelf. To get 1 SKU on the shelf at Safeway often cost as much $50,000-$100,000. At Neiman Marcus, you were essentially paying the salary of a full time employee to sit at a counter and sell your products. And products typically have 2-5 SKUs in their set. Imagine how few tech entrepreneurs could be in the Apple AAPL -1.01%’s App Store if the minimum cost to get in front of shoppers was $100,000 or more.

High fixed fees create barriers for smaller companies. This system meant that only the big, slow-moving incumbents could afford to pay the fixed fees, resoluting people to redundant, poor quality products. This is why, for decades, people were stuck with the same candy bars and home cleaning solutions. These retailers, with their slotting fees, artificially constrained competition, resulting in a long legacy of boring, stale products on the middle grocery aisles.

But a lot has changed is distribution over the past 5-10 years.

Many distribution channels that facilitate, and often celebrate, small consumer product companies have emerged. Online sales, propelled by online brand building, have matured to offer various powerful models: direct-to-consumer sites, such as Warby Park and Bonobos; subscription models, such as Trunk Club, Birchbox, Stitch Fix; and third-party ecommerce, like Amazon’s Launchpad. None of these online options really existed ten years ago. But they’ve becoming so important in driving new, better product experiences, that now the smartest big retailers are dropping slotting fees to give consumer the product they want. Whole Foods, Sprouts and even larger retailers like Costco allow smaller brands to sell without charging huge fixed fees. A bonus side prediction: those that still do charge them will soon cease to exist.

3. Emergence of Growth Levers

At the same time that huge fixed slotting fees started disappearing, the big costs to market and publicize new consumer products vanished. Social media, Google AdWords, SEO and SEM, more broadly – these variable-cost (or even free) tools changed the game when it comes to spreading the word about new products. As a consumer entrepreneur, you are no longer forced to pay huge fixed fees to be in a national weekly magazine, a TV spot or a Sunday circular, a relic from 60 years ago that was still popular as recently as 2005. Instead, smart young consumer brands can become known and drive sales by being scrappy and taking advantage of new channels. Remember Dollar Shave Club’s original hilarious Youtube ad? Dollar Shave Club now owns 5% of the shaving market and recently sold to Unilever for $1 billion.

The transformation in consumer and retail has created a phenomenal opportunity for innovative entrepreneurs in the sector. The odds of success have shifted dramatically in their favor. Numbers tell the story. As large brands rush to add fresh products that appeal to millennials, consumer M&A – the most common exit for smaller consumer companies – is booming. In 2015 alone, consumer M&A was valued at $238 billion.

Where are these big brands, and other investors, looking when looking for the next big thing, in search of the next great M&A opportunity? That will be answered in part 2 of this series.

This originally appeared in Forbes.

/Hero%20Backgrounds/Gradient-Sun-med.jpg?width=300&name=Gradient-Sun-med.jpg)