Here is the typical series of events when it comes to disruptive innovation:

- Incumbent ignores threat of disruption

- Eventually admits that disruption is a risk

- Doubles down on the most profitable business activities

- Points to small internal projects as proof of internal innovation

- Gets nervous and throws money at a hodgepodge of efforts, hoping that something sticks <see: HBR’s When Growth Stalls>

- Panics when that doesn’t work (potentially makes an overpriced acquisition)

- Replaces the CEO (or someone else to blame)

- Probably continues to lose market share

The world of private investing is walking down a very familiar path. I’ll attempt to generalize and put Private Equity in phase #3-4 as the successful funds raise more capital, resulting in bigger and bigger deals (#3) while some funds scramble to get into deals earlier (#4). Venture Capital is moving from phase #4 into #5, as VCs emphasize their “post-close value-add” (#4) and more VCs turn into venture foundries and try to become incubators (#5).

But how likely is disruption really? No new player can offer a better financial product (strong track record for investors and brand name for portfolio companies), the highest-value customers of incumbents remain satisfied, and the barriers to entry are way way too high for new entrants. These three things are undeniably true, but it’s wrong to think that they will prevent disruption. On the contrary, these three factors (performance, target segment, and barriers to entry) are telltale early signs of disruption. And here is why:

1. PERFORMANCE DIMENSIONS

Incumbent says: no new player can offer a better fund

Innovator says: your definition of “better” is out of date and there are new performance dimensions at play

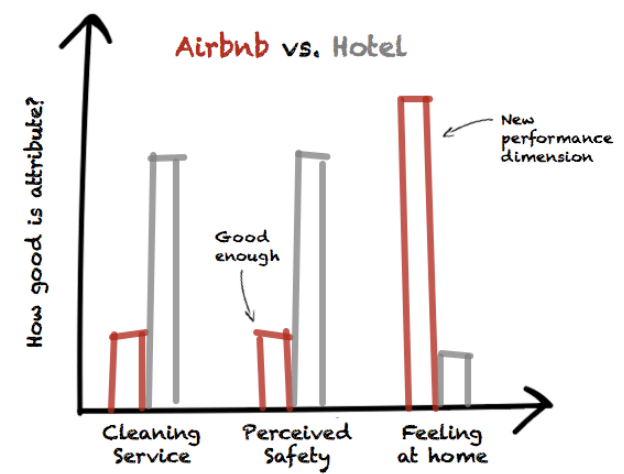

To be perfectly clear, disruptors are initially much worse than incumbents along traditional performance metrics – Airbnb had fewer amenities than hotels, Wikipedia was less accurate than encyclopedias, and Robinhood began with limited trade options (no mutual funds or options trading). Over time, these quality dimensions improved.

The key is to first win on a new dimension that is undervalued by the incumbents and important for the disruptor’s target customer. Airbnb introduced the dimension of feeling integrated in a new place, Wikipedia boasted being up-to-date and dynamic, and Robinhood introduced accessibility (driven by interface and lack of transaction fees). These are not attributes that the incumbents valued and they certainly weren’t optimized for them.

If a new entrant can differentiate on just one new and important performance metric, then all other metrics just need to be “good enough” at the offset. When it comes to private investing, LPs are looking for differentiated strategies, even in the absence of a long historical track record. The traditional performance dimensions include GP experience, team credentials, historical returns, and LP base. A new performance dimension could be exposure to a different asset class, which requires an alternative strategy. Underserved entrepreneurs are looking for a capital provider, period. If they do have choices then the new performance dimension is about the type of value-add partner – one that can offer deep insights that drive strategy in place of the typical introductions and networking event.

2. TARGET CUSTOMERS

Incumbent says: competitors are targeting a customer base that are extremely low-value to us

Innovator says: disruptors find foothold markets with non-consumers, then expand

A “non-consumer” is someone that doesn’t purchase the type of offering incumbents provide. For banks it’s both the unbankable and those that choose not to save or invest or borrow; for fast food restaurants it’s the health-conscious. There is always a non-consumer. One of the tenets of disruptive innovation is to go after a customer base that is not being addressed by the existing solution set.

Square started by going after vendors at farmers markets, non-consumers of credit card processors, and LearnVest went after non-consumers of financial advisors. Founder and CEO of LearnVest, Alexa von Tobel, has said, “Most financial plans cost about $5,000. If you are in your 20’s and 30’s, you probably aren’t ready to spend $5,000 on a financial plan to figure out what to do with your extra $5,000.” As a result, most financial planners don’t go after people in their 20’s and 30’s.

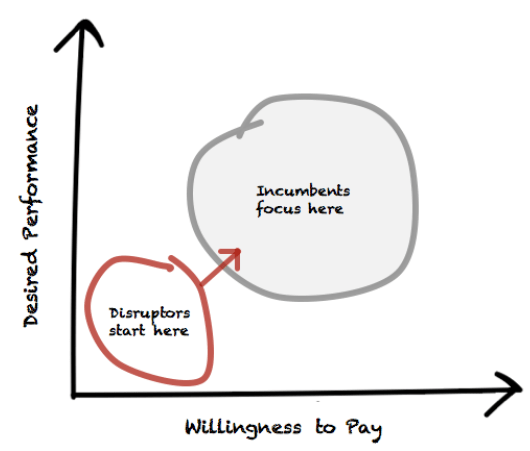

These newfound customers have a relatively low bar in terms of performance, which is generally coupled with a limited willingness to pay. Incumbents go after high margins and focus on the customers who are eager to pay the most for the very best products – with a finite number of resources, the tendency to move upmarket is not surprising.

This leaves a gap.

When successful, disruptors march upmarket and begin to capture share from the incumbents – first by going after their lowest-value customers and eventually by appealing to their higher-value customers. This happens slowly to start, then very quickly. Hotel chains couldn’t have imagined that business travelers would ever pick Airbnb. SoFi started by refinancing student loans for individuals that didn’t have a long credit history. They have quickly moved upmarket to offer mortgages and even life insurance.

Early-stage consumer is an attractive asset class that has been underserved. This is because the marginal cost of investing at this stage is too high relative to the check size and return potential. This creates the gap. Now imagine if a new entrant started offering capital to algorithmically selected emerging brands that fell outside of the criteria of incumbent investors. VCs and PEs wouldn’t bat an eye. But as those brands grow and raise additional rounds, investors would begin to notice a new player on the cap table and wonder.

3. BARRIERS TO ENTRY

Incumbent says: the barriers to entry are far too vast for new entrants

Innovator says: ha! I’ve heard that before

It’s true that private investing is hard to break into, but many now prominent companies started as disruptors with some pretty sizable barriers. I’ll rattle through a handful: Blockbuster said that inventory and a distribution network of 9,000 stores was a huge barrier-to-entry. Enter Netflix. Hilton said that brand recognition was a huge barrier-to-entry, not to mention the notion of “stranger danger.” Enter Airbnb. Lending Club had to jointly define a new security with the SEC, spending millions in legal expenses, and was forbidden from taking on new platform investors during this period. They got through it.

There are many barriers to entry in private investing – capital raising, expensive talent that is hard to recruit and hard to replicate, strong networks of executives and investors, and heuristics that have been refined over decades. But if long-standing barriers are the last defense against disruptors, then you are in trouble. Barriers have been known to crumble.

IN CONCLUSION

Disruption is a phenomenon that has occurred throughout the modern capitalist economy, and there is nothing meaningfully different when it comes to old-school private investing. Here at CircleUp, we think Helio is pretty disruptive. But we will let you decide that for yourselves.