As a child in the small port town of Hafnarfjörður, Iceland, Smári Ásmundsson enjoyed one treat in particular: a slightly sour yogurt called skyr. In the morning, he’d eat it with fresh oats; in the evenings, with fruit or jam.

And so did hundreds of thousands of other Icelanders: as far back as the 9th century, skyr has been the country’s signature food. Thick, creamy, and naturally high in protein, it sustained the Vikings through long, dark winters, and provided early settlers with a means to preserve milk. Icelanders are, and have always been, a simple, practical people — and in a land of fjords, glaciers, and jagged peaks, skyr is a simple, practical food: it is to Iceland what the potato is the Ireland.

Many years later, living in the U.S., Ásmundsson missed his childhood delicacy so much that he decided to backpocket his career as one of the world’s premier photographers and launch his own skyr business. Today, his product sits alongside Chobani and probiotic shakes in thousands of natural foods stores.

This is the story of how Smári Organics got into every Whole Foods in America.

The Yogurt Viking

Smári Ásmundsson spent his earliest summers delivering newspapers so that he could afford a camera. Years later, after briefly studying business, he’d embark to the United States and enroll at Santa Barbara’s prestigious Brooks Institute of Photography.

What followed was a career as a one of the world’s premier advertising photographers: jetsetting across the globe, the large, bearded man became eminent in his field, shooting for clients like Volkswagen, Rolex, and Genentech.

But when his first son was born, Ásmundsson’s thoughts were consumed by nutrition. “I became interested in improving our diet,” he said in an interview, “and I was discouraged by the conventional foods that were here in the United States.”

Fortuitously, his mother arrived, bearing a suitcase full of Icelandic goods, including several large tubs of skyr.

Skyr, realized Ásmundsson, was nutritious, wholesome, and a formidable alternative to the “sugary crap” pervading the American culinary landscape. So, like any self-sufficient Icelander, he set out to make it for his son.

To learn the ropes, he journeyed to the eastern Iceland town of Egilsstaðir and shadowed an 82-year-old dairyman. The skyr maker offered simple advice: “Get the best milk. Skim the fat. Add live cultures. Let it set. Strain the liquid. When it looks really thick, strain even more.”

In May 2011, with little real-world business experience, and nothing more than a traditional recipe for skyr, Ásmundsson decided to start a yogurt company.

Diving In

Ásmundsson’s knowledge of the natural food industry was limited, but he knew that contacting Whole Foods would be a good place to start.

With 88,000 employees, $14.2 billion in annual revenue, and 421 locations, Whole Foods represents more than 40% of all self-identified “natural food” stores in the United States. Whereas the majority of other natural food stores are relatively small (averaging around 2,000 square feet per location), the typical Whole Foods market is anywhere from 20,000 to 50,000 square feet, and houses a much wider, diverse range of products.

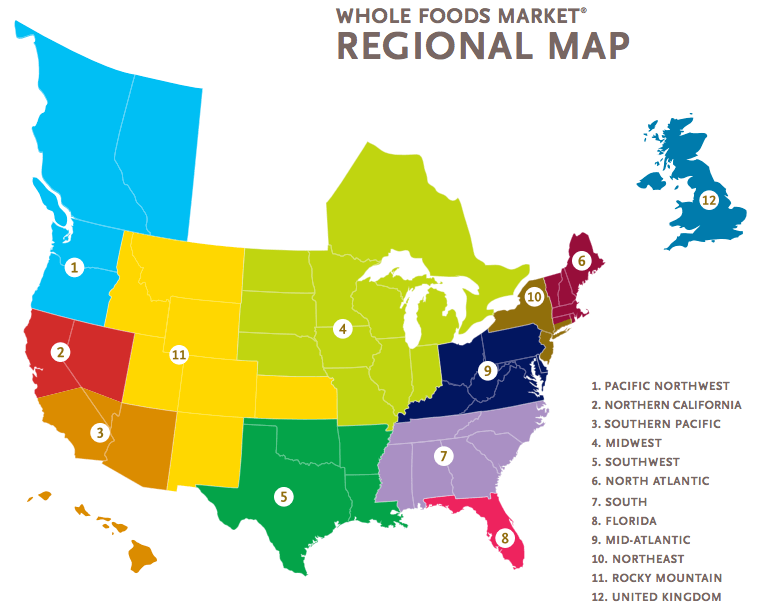

The chain delineates its markets into 12 different “regions” — each of which is keen on supporting local products. After doing a little research, Ásmundsson learned that the best way to approach Whole Foods was to contact the buyer closest to him: he dug up the phone number for Northern California’s dairy buyer, and gave him a ring.

Via Whole Foods

“I’m from Iceland, and I’m interested in starting a true sykr company,” he told the buyer.

“You’re not going to believe this, but I think I’m more excited about this idea than you are,” the man responded. “The sooner we can meet, the better. We’ve been looking for something like this.”

A week later, the two met. Ásmundsson had no package, no design, and no company name; all he brought with him was a cardboard box full of yogurt he’d made in his kitchen the night before. The buyer saw the product’s potential, but it needed a lot of work to be ready for the shelves: certifications, packaging, financial backing, and, most pressingly, a production facility.

“When you’re ready, just give us a call,” said the buyer. “We think this will be great.”

Overwhelmed, Ásmundsson turned to his friend, Douglas Stewart, and asked him to come on board as a co-founder and partner.

A Little Help From a Friend

Twenty-five years earlier, as a student at Stanford University in the early 90s, Stewart had spent a year in the rainforests of Brazil studying Amazonian deforestation.

While there, he formulated an idea: “There were all these exotic fruits nobody in the U.S. had ever heard of,” he says, “and I thought, ‘Somebody should make them into a commodity that Americans will eat, then give back a portion of the profits to help save the trees.’”

In 1994, two years after graduating, he launched Howler Products, a line of organic sorbets and gelatos using exotic rainforest fruits from South America. Like Ásmundsson, he didn’t know much about business, distribution, or branding, and was only armed with a vague theory about a product that would make the world a better place. Also like Ásmundsson, he decided to approach Whole Foods first.

Back then, he says, the process of getting into a Whole Foods was different, and even more localized:

“An individual store buyer could make a decision on a product, put it on Whole Foods shelves, and sell it the very next week in that store (this is no longer true). I approached a guy who worked in the Palo Alto store, near campus, and he agreed to stock my product. From there, I got a meeting with Whole Foods’ regional dairy guy, and the products were put in 3 other Whole Food stores in Northern California.”

By Spring of 1995, partly thanks to a highly successful Stanford University press release, Stewart’s sorbets and gelatos were in 50 stores across the United States. The following year, Stewart purchased a 4,000 square foot factory in San Francisco, and was churning out 30 gallons of product per day. Eight years later, his factory was producing 5,000 gallons a day, and Howler Products had become the #1 selling organic sorbet in the United States.

Still, says Stewart, the organic foods market was miniscule compared to what it is today. “To put it into perspective, my product was on every shelf in virtually every natural foods store in America — and I had less than $1 million in sales during those times,” he says.

When bigger brands recognized Stewart’s success, they replicated his model; by 2004, Howler Products had been forced out of the market. He spent the ensuing years launching several other food and beverage ventures, including an award-winning wine company that he later sold for several million dollars.

“After that, I told myself I’d never get back into the food business,” says Stewart, “but that if I did, it would be for yogurt: I thought it had a lot of runway.”

The Rise of Smári Organics

When Stewart received the call to join Ásmundsson in the Summer of 2011, he jumped at the opportunity. Since launching Howler Products, the organic food industry, as a whole, had grown from a $1 billion to a $26.7 billion industry — but since he’d been through the ropes before, he was able to swiftly assemble a plan of action.

While Ásmundsson thought he needed about $250,000 to get off the ground, Stewart estimated they’d need more on the order of $2.5 to $5 million (“Getting yourself in everyone’s mouth is a very expensive game,” he says). Initially, they chose to bootstrap the upfront costs.

After naming the company Smári Organics, after its founder, the duo then tapped into Ásmundsson’s network of talented designer friends to craft the packaging and labels, which featured “aurora borealis themed stripes.”

When they met with Whole Foods’ Northern California dairy buyer again in early 2012, he was not only excited, but wildly supportive. “He said, I’m going to kick this up the chain to national; when you get bought, I want to be your first region,’” recalls Stewart. But the team had a massive challenge ahead:

“We were hitting wall after wall when it came to getting the product made in a factory. It required very specific equipment nobody in the U.S. owned, or had ever used before. If we really wanted to make skyr the way they made it in Iceland — the right way — we needed this equipment.”

A trying year ensued, in which Ásmundsson and Stewart raised capital through CircleUp and scouted a location for a factory. Finally, by the end of 2012, Ásmundsson and Stewart had imported the necessary equipment from Europe, and found “the perfect production facility,” right in the middle of Wisconsin’s Organic Valley — a location that has served as the nucleus of America’s booming yogurt market over the past decade.

Via Smári Organics

Being bought by Whole Foods, a chain with massive scale potential, meant that Ásmundsson would have to turn his kitchen-made dish into a much larger operation. To do so, he’d need to significantly re-tailor his recipe, while still staying true to its roots. He settled on a system in which he sourced milk from organic, pasture- based Jersey and Guernsey cows, skimmed the cream from it (skyr is traditionally made with nonfat milk), then inoculated it with live cultures, and ran it through a specialized strainer that removed a high percentage of water without compromising the yogurt’s creamy texture. They started with four flavors (Pure, Vanilla, Strawberry, and Blueberry), each of which came in a 6-ounce container.

At the time, most Whole Foods stores already stocked one other skyr yogurt, Siggi’s, which had launched a few years prior to Smári Organics — but it did not utilize the specialized machines used in Iceland.

“We’re the only yogurt company in the U.S. with this machinery,” says Stewart, who won’t expand on what the machines are, since they are among Smári’s core intellectual properties. “It’s slower, way more expensive, and — oh my God, so much harder to manage. But, the process we came up with is so good that people from Iceland tell us it’s the best Skyr they’ve ever tasted.”

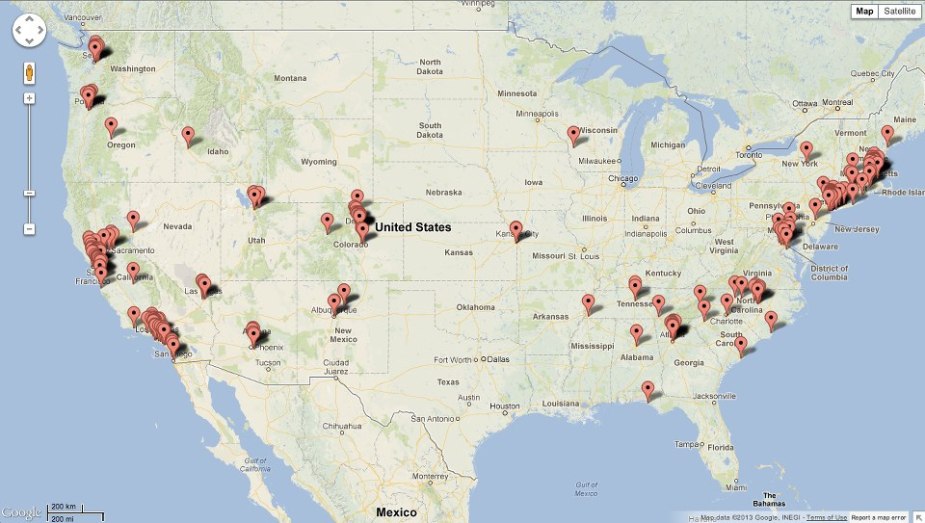

When Smári Organics finally opened its doors in January 2013, they had standing orders from half of the Whole Foods in the country — at the time, some 175 stores. By mid-2013, they’d expanded to about 300 stores:

Smári’s distribution in April, 2013

Getting onto the shelves at Whole Foods opened other doors for Smári: they were soon picked up by Costco, Kroger, Safeway, The Fresh Market, National Co-op Grocers, and “numerous independent stores and smaller chains.”

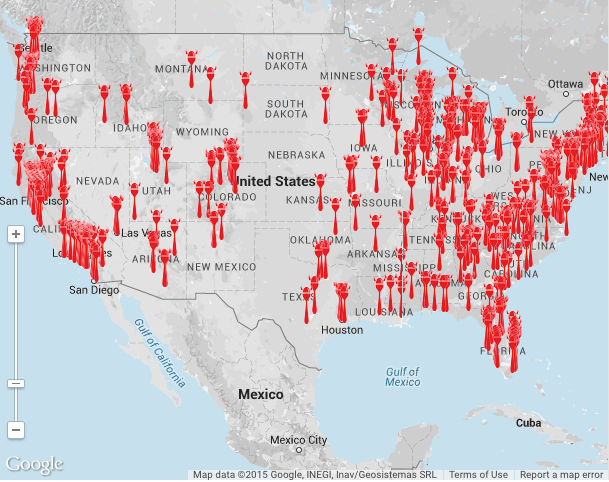

Over the course of two years, they added four new flavors (Nonfat Coconut, Peach, and two Whole Milk flavors), and more than doubled their distribution, to 777 stores nationwide — a growth of 151%:

Smári’s distribution in April, 2015

“Whole Foods sees itself strategically as a pioneer of new products, and new ideas — they’re an incubator of foods that are good for you, environmentally friendly, and produced in socially and economically sustainable ways,” says Stewart. “And they’re able to slam you into distribution and scale you like no other natural foods chain can.”

The Challenges of Scaling Quickly

Today, largely thanks to Whole Foods, Smári Organics ships to around 20 large warehouses a week using 5 major distribution companies. But scaling so quickly, says Stewart, has come with its own set of challenges:

“In the food business — especially yogurt — you need a lot of product to succeed. When you make a 1,000 gallon batch, that produces about 150 gallons of yogurt, or 500 cases of finished product. That’s a pretty big loss of initial ingredient, and input cost is high. We prefer to make 4,000 gallon batches that produce 2,000 cases of product — about $30k worth. That’s the bare minimum you can make before you can possibly think of any margins.”

Smári’s first Whole Foods shipment leaving the dairy warehouse (December, 2012)

In addition, Whole Foods has pushed Smári to adopt certain labels, in order to sell more units.

“We didn’t necessarily intend for Smári to be a kosher, gluten free, or grass-fed company, but Whole Foods thought those labels would entice more people to buy the yogurt,” says Stewart. “They push producers to adapt certain labels, and go through the certification processes.” In doing so, the chain has influenced how products are marketed — on its shelves and beyond.

As a smaller product in larger stores, Smári also must compete in a market that Stewart calls a “kleptocracy.” When courting a major grocery outlet, a company must pay slotting fees — or fees the outlet charges to stock a product on its shelves. These range from $25,000 for regional stores, to more than $250,000 in “high demand markets.” The company must not only pay this fee, but give the store cases of free product (called “free fill”), that the store then sells at full price and pockets the profit on. To date, Smári has spent $327,000 on these costs.

In an effort to market niche goods, a store will also often overextend its discount periods — for instance, marking down a product 25% for four weeks, when the initial agreement with the distributor was for one or two weeks. The margin, in these cases, is pocketed by the store. Ultimately, Stewart says these tactics benefit the food business’s “big players,” while harming the little guys.

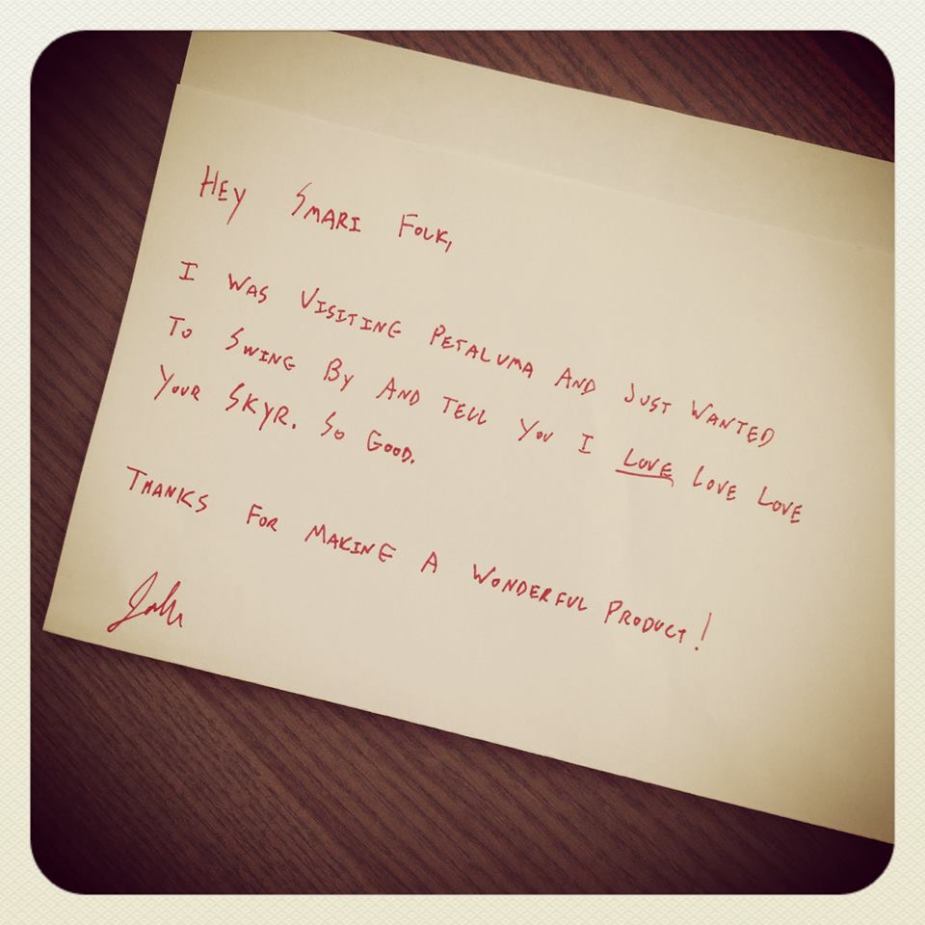

A note left on the doorstep of Smári Organic’s fan Petaluma (Northern California) headquarters

“Building a food brand costs a lot more than it should,” he says. “The big players in food — Nestle, Unilever, Dannon — aren’t as impacted by these things: they have the budget and marketing muscle to put a product on 30,000 shelves all at once, and have a 3,000 person sales team to sell it.”

Luckily, Whole Foods is in the rarified group of big stores (along with Walmart and Costco), that does not charge slotting fees, or demand free crates of product. Instead, the store relies on testing the waters with products at a regional level, before committing to them on a national scale (in this sense, Smári is an anomaly).

Additionally, there is a incalculable value to being a small food brand that comes in the form of being a part of a special community.

“At the end of the day, I like making a product that my family and friends can buy locally, and that I can feed to my kids,” says Stewart. “It makes me feel like what I do for a living has a tangible, positive impact on people’s lives."

/Hero%20Backgrounds/Gradient-Sunset-I-1900x1080.jpg?width=300&name=Gradient-Sunset-I-1900x1080.jpg)