Companies that sell food, clothes and packaged goods are less profitable than companies pushing software and online services, right? Not exactly.

Saar Gur, a general partner at Charles River Ventures, a multi-billion technology venture capital fund, recently published detailed research challenging conventional wisdom about the potential for consumer product companies. Gur’s research (reproduced with expressed permission) wrangles data from private and public markets to dispel many commonly held myths about consumer and retail companies. As Gur points out, the public markets are full of consumer and retail companies that grew fast, operate efficiently, and demand incredibly favorable valuations. Let’s look at some examples from Gur’s research.

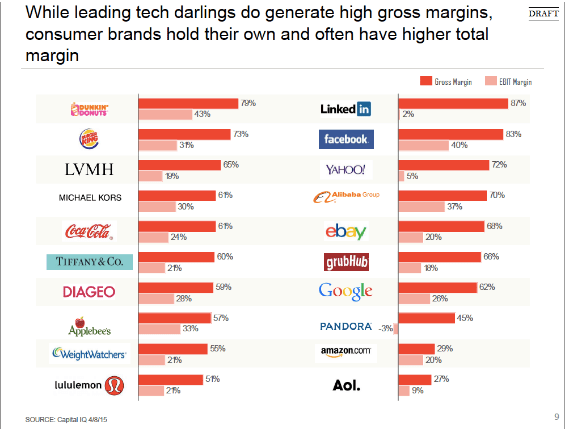

Dollars for donuts, Dunkin’ is a more profitable company than Google, LinkedIn, eBay or even Facebook. On an EBIT (Earnings Before Interest and Taxes) comparison, the Gur’s research shows Dunkin’ Donuts beats Google by 17 percentage points, LinkedIn by 41, eBay by 23 and Facebook by 3, respectively. This is not an anomaly. Many of the most recognizable consumer brands regularly post higher profits margins than leading technology brands and some trade at higher multiples than their tech counterparts.

Despite this, emerging consumer brands selling food, apparel or packaged goods have had a tougher time raising capital in the early-stages than their counterparts in tech over the last decade. In 1995, consumer companies received 13 percent of all venture dollars invested, while in 2014, only 8 percent. Consumer brand companies make up 19 percent of U.S. stock market value, pointing to an unbalanced tipping scale.

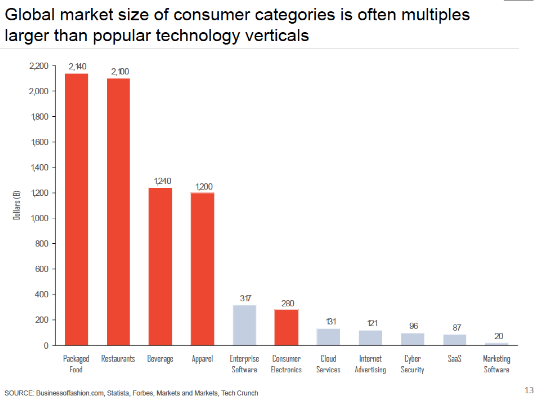

And that’s just the U.S. stock market. Many consumer categories have global market sizes orders of magnitude higher than even the largest tech verticals.

For decades, consumer product and retail entrepreneurs have struggled to raise capital efficiently despite historically strong returns. This lack of capital has made it harder to innovate — imagine where tech would be without Silicon Valley. When it’s harder for emerging companies to innovate, we’re left with products like Clorox Bleach, Twix Candy Bar and the Big Mac — terrible products that have not changed in decades.

The good news is that the gap in capital for consumer and retail entrepreneurs is starting to close. As more entrepreneurs get the funding they need to create new, authentic products, smart investors will find more opportunities for strong returns. The winners in this virtuous cycle? Entrepreneurs, investors and consumers. The losers? Fortune 500 consumer companies that aren’t innovating.

Let’s take a deeper look at why we’re already seeing a major uptick in capital flow to early-stage consumer and retail entrepreneurs.

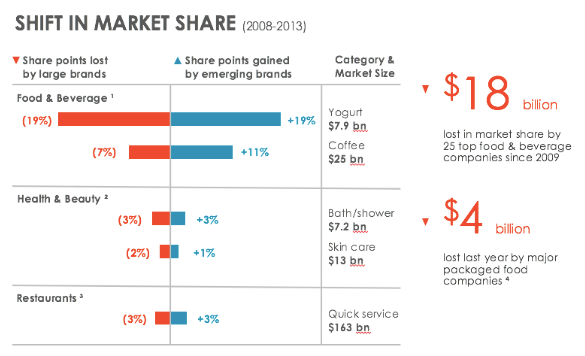

The Personalization of the Consumer

Go to any supermarket beer aisle today and you’ll see dozens of brands on display. Two decades ago, there would perhaps have been a dozen. Four decades ago, maybe six. Consumers are demanding a more personalized offering that meet their unique needs. Consumer taste for beer has shifted rapidly to microbreweries and regional brews that offer a combination of high quality, unique attributes — barrel-aged coffee porter, for example — and tell an enticing brand story. As goes beer, so goes most all of consumer and retail. Among the top 100 consumer brands in the U.S., 90% have been losing market share and 68% have experienced falling sales. Some $18 billion in sales shifted from large to small companies from 2009 to 2014 across all consumer packaged goods categories, according to a report by Boston Consulting Group and IRI.

Considering the overall massive size of the consumer market, that’s a huge shift for a five-year span. And the “Personalization of Consumer” is only accelerating. As consumers increasingly move from large brands to small brands, there is an enormous opening for entrepreneurs to create emerging, authentic, mission-driven brands that add real value.

Significantly Better Capital Efficiency Entrepreneurs building consumer and retail businesses utilize capital more efficient than tech. According to Crunchbase data, between 2010 – 2014, the average amount raised for a Series A was $7M, $15M for Series B and $27M for Series C. All of that funding ($49M) typically happens before a tech company reaches $10M in revenue. Contrast this with the data we’ve gleaned from CircleUp, including data on over 10,000 early-stage consumer companies. We see companies with revenues between $1- $10M typically only needing to raise $2M or less in a Series A or B — less than $10M in total. You’ll be hard pressed to find a consumer product company that has raised $50M in growth equity before getting to $10M in revenue. In consumer, you don’t need to burn that much cash to build a significant business. (Entrepreneurs — if you’re raising tech-sized rounds to build consumer companies, you’re doing yourselves and your investors a disservice).

So the idea that tech companies are more capital efficient is a common fallacy. While gross margins in some cases are high, selling, general and administrative expense (SG&A) tends to be off the charts for tech companies – leading the overall cash flow characteristics to be extremely poor. Even established tech companies have one of the highest median SG&As of any industry. Think about it: their manufacturing (engineering, design) is all “in-house” while consumer companies typically outsource. At that stage, too, the consumer companies are turning revenues in the mid-seven figures even as many of their A-round tech counterparts have zero revenue.

As they mature, consumer startups can grow faster per investment dollar than in tech. Take Krave Jerky, Dry Bar, and Shake Shack, which all boast eight and nine-figure revenue run rates. None raised more than $100M before an exit, like in tech. Compare that to Big Data startup Cloudera which has raised over $1B (as in billion) in venture backing but only booked revenues of $200M in 2015.

The Growing Power of Direct Channels

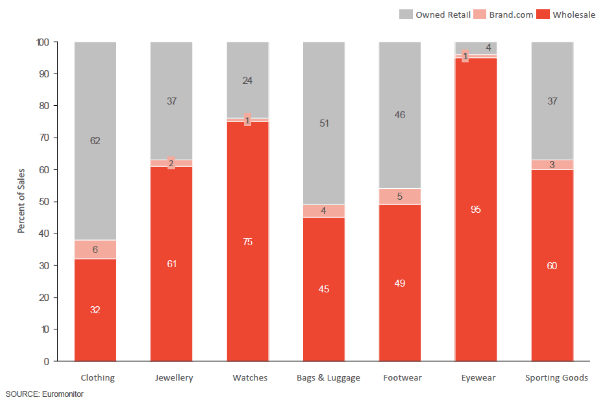

Traditionally, consumer entrepreneurs have had to go through wholesalers, large retailers or catalog intermediaries to achieve scale. These intermediaries charge rents in the form of distribution costs, markups, slotting fees and other costs that are paid by the companies (and eventually, the consumers).

Wholesalers in the middle have captured tremendous revenues. In sporting goods, for example, 60% of sales are still through wholesale channels. In eyewear, it’s a whopping 95%.

But this is largely shifting, because cutting out the middleman has never been easier, in turn making it easier for emerging consumer companies to thrive. Many of the most successful recent brands have leveraged this approach with excellent outcomes. Bonobos and Betabrand are two apparel companies that gain the majority of their sales directly via their websites and maintain close connections with loyal followers.

Increasingly, brands selling directly can narrow sales efforts to precise personae and market far more efficiently to those groups. Warby Parker has built high-volume, high-sales physical locations to serve as adjuncts and marketing arms for the online business. That’s not to say the stores aren’t profitable. Warby’s stores drive $3,000 per square foot, more than Tiffany’s and close to Apple.

Today, savvy entrepreneurs can create a global presence without expensive media buys or building brick-and-mortar locations. Scaling a consumer brand directly with target customers is more possible than ever before.

Scaling to $1 Billion in Sales

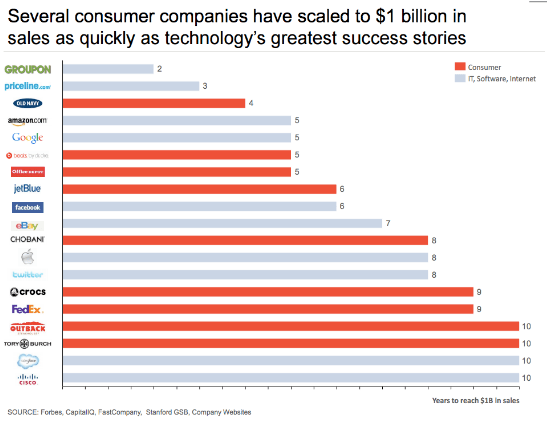

“Growth is in Tech” is a misconception I hear all too often. Consumer brands can actually scale revenue just as quickly as the fastest growing tech companies.

For example, as Gur points out, Old Navy grew revenues to a $1 billion run rate in only four years faster than Google and Amazon (5 years), Facebook (6 years), Apple (8 years) and Salesforce (10 years). Global consumer brands can indeed be dominant forces. Nike, Starbucks and Coca-Cola each control over 50% of their corresponding market just like Apple and Google in their respective niches.

There has been a major upsurge in VC and media attention to tech in the past few decades, but the big picture shows consumer businesses accounting for much of the impressive, stable growth.

Exit Opportunities Abound

In general, emerging brands have strongly resonated with Millennials and Generation X. To tap into that consumer shift, large consumer brands launch aggressive campaigns to acquire growth via acquisitions, plugging those small brands into their vast distribution channels. Big brands have spent tens of billions to buy fast growing ones, including Ben & Jerry’s, Burt’s Bees, Lagunitas Brewing and Kashi. This has translated into numerous strong exits for founders. For example, Lagunitas Brewing quietly sold a 50% stake to Heineken in 2015 at a reported valuation of $1B.

Not surprisingly, angel investors in consumer products are awakening to these opportunities, which have returned an average of 3.6 times an investment in 4.4 years, according to a study by the Kauffman Foundation’s Angel Investment Performance Project. Most venture funds have a five-year investment window and a ten-year fund duration. In comparison, a 4.4 year turnaround is lightning pace.

The most common exit in consumer and retail is selling to an innovation-starved strategic. The M&A market in consumer and retail was $235B in 2015, about 60 percent greater than M&A in tech, according to PWC research. The IPO market for consumer and retail might surprise you, too. Recent consumer product IPOs have created bigger businesses per VC dollars invested than tech IPOs. If we look at last-twelve-months (LTM) revenue at time of IPO relative to pre-IPO capital raised, here’s what Gur’s research finds: Skullcandy was twice as big as GrubHub; GoPro was twice as big as Facebook; and Potbelly Sandwich Works was twice as big as Zendesk.

Of course, the success of Apple, Facebook, and Google is unparalleled, but they represent an incomprehensibly small percent of all tech company founders. In other words, the tech business is a bit like playing the lottery.

On the other hand, entrepreneurs who are seizing the opportunity presented by the Personalization of the Consumer may face far better prospects for success than they even realize. For every next Facebook, there are likely a dozen or more Annie’s Organics that will prosper into powerful businesses improving some of our nation’s most important and personal products.

This article originally appeared in Forbes.