The world of consumer goods is changing at a breakneck speed. This isn’t a shocking revelation to anyone who’s worked in or around the sector. Consumer tastes are becoming more and more fragmented and big incumbents continue to lose market share to upstart brands. It’s often difficult for these incumbents to figure out how to respond. On paper, a lot of big CPG companies look great. They’re full of smart people, they have well recognized brands, international distribution networks, and a lot of money in the bank. Despite all this, many of these brands have seen their sales stagnate or decline over the past several years.

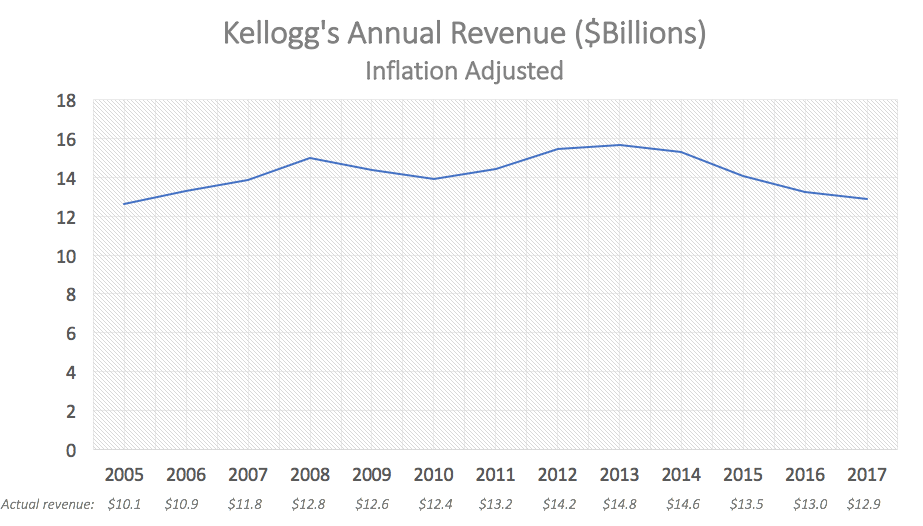

Kellogg’s is a textbook example of Big CPG in trouble. On paper, Kellogg’s has a lot going for them including some iconic brands. In reality, their recent financial performance tells a lackluster story.

Before I dig in here, I want to say upfront that I don’t have all the answers (or even most of them). I’m the CEO of CircleUp – a startup with 65 employees- not one with 30,000 employees. The insights I hope to share are gathered from over a decade working in consumer investing and helping consumer companies grow, but they’re ultimately insights from the outside looking in. The title of this piece says “Kellogg’s” but you could drop in the name of PepsiCo, Estee Lauder, Nestlé, Kraft-Heinz or countless other big brands. This isn’t about just one company, it’s about the dynamics that exist for virtually all CPG incumbents. A lot has been written, by me and others, on the challenges these large incumbents face, but very little has been written about their options for success. I find that topic – the solution– to be both more difficult and more interesting to explore.

How Big CPG thinks about the future

Profit = revenue – costs. Consumer companies can increase profit and deliver shareholder value (their fiduciary responsibility) by either growing in revenue or cutting costs.

Increasing revenue

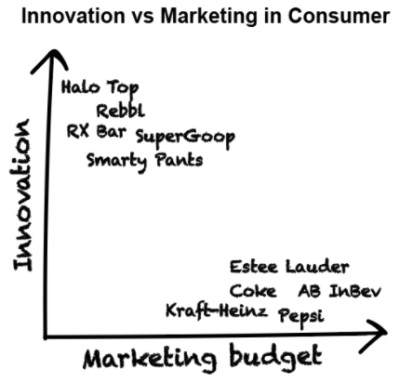

“We’re also investing in advanced manufacturing technologies like our proprietary frying innovation that can reduce the amount of fat in a potato chip by 20%.” This is an excerpt from Pepsi’s 2016 annual report and highlights how a lot of big consumer companies think about innovation and growth. Consumers want less of x so let’s take our already existing products and reduce the amount of x in them. Consumers want more of y, so let’s add more of y to one of our product lines. This is one element of Clay Christensen’s work on the innovator’s dilemma: sustaining innovation vs disruptive innovation. Christensen’s research found that incumbents tend to make incremental improvements to their existing products. Disruptors, on the other hand, enter the market by offering a product that wins on a new performance dimension and captures non-consumers. Eventually that disruptor begins to capture a small portion of the incumbent’s market share. Because the profit pool at that level is often so small (as a %), the incumbent doesn’t bother responding, but the new entrant gradually captures more and more share until they pose a real threat. By the time the incumbent recognizes this threat, it’s too late to respond. In CPG, we’re seeing this not just with one or two emerging consumer brands, but thousands.

Big CPG also spends huge amounts of money to get consumers to buy their already existing products. In 2017, Anheuser-Busch InBev spent $8.4 billion on sales and marketing activities. $8,400,000,000 dollars. That’s over 25x the amount they spent on research and development. Rather than asking themselves what consumers like, AB InBev spent far more trying to convince consumers that they should like already existing products. It’s no wonder that this climate gave rise to thousands of craft breweries that ate into the market share of AB InBev and other big brewers. A decade ago the top ten beer brands in the US made up nearly 66% of market share- that has shrunk to 50% today. This spending on marketing is representative of the way big consumer companies think about innovation. In my experience, the more a company loses their innovation the more they increase their advertising budget.

Cutting costs

If Big CPG can’t increase revenue, they’ll cut costs. Recently, some consumer companies have succumbed to the so called 3G effect- a strategy pioneered by Brazilian mega fund 3G Capital which involves the merger of big CPG companies and the dramatic slashing of costs to increase profits. The most famous example of this is the Kraft-Heinz merger. 3G Capital managed to cut costs in this merger but did almost nothing to actually foster innovation. M&A for the sake of cost cutting is a race to the bottom and a fool’s errand. You can’t cut beyond 100% but you can grow by more than 100%. While cost cutting and efficiency gains are sometimes necessary in a global company like Kellogg’s, those profitability gains should be entirely reinvested in the future growth of the company. It’s time to shift the market’s focus towards long-term growth and away from short-term cost-cutting. The need for longer-term positioning is imperative in a changing world.

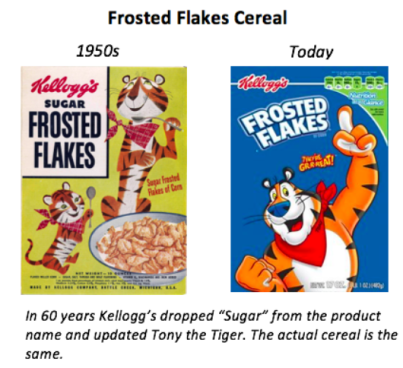

What I would do differently

On day one as CEO of Kellogg’s, I would take a hard look in the mirror and I would ask myself which Kellogg’s brands are still relevant and can grow. I recently had a conversation with a former VP of a major CPG company and he said that Big CPG is guilty of thinking that everything can be relevant if they bring the right news to it. He’s right. I would acknowledge up front that we have certain brands and products that are cash cows now-but are slowly dying. For example, in a world that is increasingly health conscious, there will come a day when Frosted Flakes are no longer relevant. Trying to make it relevant with a new version of Tony the Tiger or an expensive ad is missing the forest for the trees. A more proactive step is to sell the legacy cash cows that are dying and invest the cash windfall into innovation. This week I was in another discussion with a 20 year veteran from a Fortune 100 consumer company who said “I think in 10 years our company will no longer exist. It will be broken up.” Conversations about selling legacy brands will make a lot of consumer executives squirm, but they are conversations that need to happen. Cutting the dying cash cows is the hardest but probably most important step in righting the ship.

After deciding which of our legacy brands to divest, my next step would be to publicly announce that we will shift focus away from cutting costs and towards investing in a culture of innovation to actually grow the business. This will likely cause our stock price to go down in the short term, but in the medium to long term this will help our company tremendously. Simply put, we can’t survive by cutting costs forever. We need to grow. Our culture of innovation will be built and promoted in a variety of ways. What follows isn’t a sequential list but rather initiatives that should be pursued in parallel:

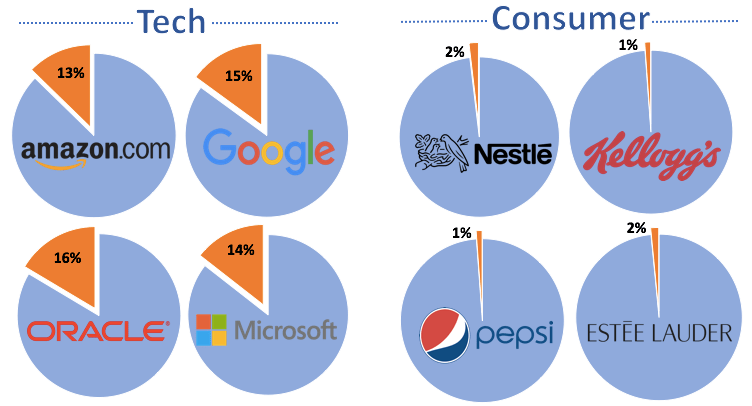

1) Research and Development. We will signal to Wall Street that we are going to focus on growth and innovation, not cost-cutting. We’re going to go through a rehaul of the R&D process and pipeline and we will dare to dream bigger. In 2017, Kellogg’s spent $148 million (1.1% of net revenue) on R&D. This may at first sound like a lot, but for comparison, Google spent $16.6 billion (15% of net revenue) on R&D during the same time period. The dichotomy between tech and consumer spending on this front is highlighted in the chart below.

Source: Company 10-Ks for 2017

It’s no wonder that one of these companies has been making Frosted Flakes the same way for over 60 years (with goofy TV commercials for most of that time) while the other started as a search engine and now builds phones, maps, and self-driving cars. Imagine how comical it would be for a tech company to sell the same product for 5 years, let alone 50. R&D is not just about coming up with a new flavor or lowering the fat content of an existing product. As one big CPG veteran told me recently – “consumers don’t care about ‘whiter whites’” anymore”. It involves building an adaptive infrastructure that truly listens to what consumers want and then relays that information to development teams in a way that allows them to be agile and effective. We need to have an R&D team that is focused on the category and consumer, not the product. Instead of Pepsi thinking about a lower fat potato chip, they need to be rethinking the snack category as a whole. Why is it insane to imagine AB InBev developing a beer that doesn’t cause hangovers, but it isn’t crazy to imagine Elon Musk sending people to Mars? Why is it laughable for Clorox to invest a billion dollars into developing a non-toxic, safe substitute for bleach, but it’s normal to imagine investing $15 billion into Uber- a company that is trying to replace all taxis in the world? Those comments are meant to push public CPG CEOs, not to degrade SpaceX or Uber.

Good R&D also involves keeping your ear to the ground for great ideas that may already be out there. There could be a toothpaste in India that would revolutionize the way we think about toothpaste in America, but we’ll never know if we aren’t listening. For an example of what can happen without this R&D infrastructure, look no further than the pharmaceutical industry where Big Pharma companies are now having to pay to outsource innovation because they can’t foster it in house. CPG could become Big Pharma.

2) Incubation. In addition to investing in and partnering with great consumer companies, we will provide space and expertise in house to help them grow. Kellogg’s recently partnered with Conagra Brands and the City of Chicago to invest in a $34 million food incubator that is expected to support around 75 companies, 80% of which will be in the snack category. This is definitely a step in the right direction, but I’d want us to go bigger and take the operation in house. I’d like to incubate 100+ companies per year from a wide variety of categories and become the Y Combinator for consumer. This will be a win-win. We get to help great consumer companies grow and these companies get to leverage our expertise and infrastructure.

3) Venture capital. Too many CPG companies only invest in brands once those brands are 5+ years old and end up paying a huge sum as a result. I would change our mandate to invest in companies that will be interesting 10 years out – not just companies that we think are going to contribute immediately to our revenue or existing product strategy. We need to take the long view here and data plays a big role. Kellogg’s will not identify innovation just by sending a dozen people to Expo West. We need a non-commoditized data and technology solution that can help us identify breakout brands early by looking at their growth potential- not their Expo sales booth. Kellogg’s is actually ahead of most CPGs when it comes to venture in that they have a venture arm of $100 million. But this is still too small. I would start by having our venture arm manage assets of $500 million (less than 4% of net revenue but still 50x the AuM of many CPG corporate venture arms) and tell them that they are going to invest in 200-300 companies, focusing on early stage companies with less than $10 million in revenue over the next 2-4 years. If that sounds insane, look at Google’s GV for some inspiration. They build a diverse portfolio to foster innovation from many and sometimes unexpected angles. If tech VCs can have a portfolio of hundreds of companies, so can we. A venture arm in consumer is nothing new. Many large CPG companies have launched venture arms, but most of these consumer VCs only plan to invest around $5-$10 million across 3 to 4 companies. Then the CEO loses his or her nerve, succumbs to the pressure of short-term cost cutting, and bails on the strategy. We will dare to take the long view.

Beyond just capital, I would create a structure that provides these companies resources and support to help them be successful. We will create a program to allow for externships between Kellogg’s (and possibly our partners) and the portfolio companies we invest into. Hardly a week goes by that I don’t receive an email from a brand manager, marketer, supply chain expert, or others at one of these public CPGs who are looking to move to a smaller company. This externship program will be an asset for the smaller brands while also acting as a retention tool and bringing innovation back to Kellogg’s.

4) M&A. Despite my criticism of the 3G effect, I’m not against M&A. I’m against M&A for the sole purpose of stripping cost as a strategy to deliver long-term shareholder value. My belief is that in 10 years the revenue from the core existing products of many consumer companies will be much smaller than it is today. These products won’t be replaced by 1 or 2 new products, they’ll be replaced by hundreds – or thousands. That is the fragmentation of the consumer or what we have called in the past the Personalization of the Consumer. Big CPG can either buy these products (at an earlier stage) or lose to them. I would want our company to ingest a lot of smaller brands rather than forking out hundreds of millions (or billions) of dollars once these brands are already big. We will need to also invest in the infrastructure necessary to work with many more brands and benefit from their growth. The brands will join the Kellogg’s family rather than threatening it.

5) Partnerships and joint ventures. Every now and then you will hear about a joint venture or partnership in consumer but they are few and far between. Why? I think a lot of times big consumer companies fear that partnering with another company will mean splitting profits which can negatively impact bottom line. This is not a productive attitude. You see examples of successful partnerships in almost every other industry- whether it’s Google teaming up with Walmart to offer Walmart products on Google Express, or Chrysler teaming up with Waymo to work on driverless cars, partnering with a variety of stakeholders can often help foster the best innovation. I also think there is a big opportunity to partner with other consumer companies to foster education in the sector itself. We could host conferences that bring together the best consumer entrepreneurs and the brightest ideas and we would all benefit as a result.

Why this matters

If my plan as CEO were effectively implemented, I think we would see three powerful effects. Firstly, by making more small bets on more emerging brands and building a culture of innovation, Kellogg’s would become a dominant player in consumer goods. They will no longer fear being displaced. They will be the ones creating and harnessing the disruption. Secondly, this roadmap would ensure that the best products make it into the hands of consumers and that everyone has access to a wider variety of foods and healthier options. Finally, by building this infrastructure, Kellogg’s would be able to assist entrepreneurs with their distribution, brand, supply chain, and team. As these companies grow and succeed, this will also result in increased value for shareholders. Consumer is an extremely inefficient market, but Kellogg’s can be the public company that helps change that.

Again, it’s easy for me on the outside looking in to suggest strategies like this. It’s much harder to implement them when you’re on the inside looking out. I think a lot of Big CPG CEOs probably do have bold ideas that would help their companies in the long run, they are just unable to pursue them in an environment that obsesses on the short term – a board that demands immediate cost cuts and a market that demands immediate stock value. So these CEOs are hamstrung and left to rearrange chairs on the deck of the Titanic while the whole ship is sinking. They fear that if they do too much to try to save the ship they won’t last long. Gates, Musk, and Bezos are free to be visionary and push their companies to the cutting edge of innovation while Cahillane (CEO of Kellogg’s), Hees (Kraft-Heinz), and Quincey (Coke) have to work within the box they are put in. I truly hope that big consumer companies will begin to innovate, be creative, and listen to what consumers want- and that corporate boards and Wall Street will realize the long-term value of these things. If the industry doesn’t evolve, you never know, Google might just step in with the next big breakfast cereal.